I love the words of cooking almost as much as cooking itself. Behind each term lies a taste, a memory, a feeling, or a particular way of doing things. This A to Z of French cuisine, published in installments, doesn’t aim to be exhaustive. It’s more of a mental and flavorful map of what nourishes me—both literally and figuratively.

Letter by letter, I trace a subjective path through words I love, words that spark my curiosity or whet my appetite. Each entry will be explored in detail, often paired with a recipe or a practical tip. A way of taking food quite literally.

Here are T for Terrine, U for Uniformisation, V for Vol-au-Vent, W for Wagon-bar, X for Xylénique, Y for Yaourt and Z for Zou !

T - Terrine

The word terrine originally refers to an earthenware dish, fairly deep and with a lid, used for cooking and preserving certain preparations. By extension, it came to designate the contents themselves: terrine de pâté de foie, de lièvre, de canard, de lapin, terrine de poisson, de bar, de brochet ou de saint-pierre.

Zola captured the image: “(…) right beside her, under her hand, were the larded veal, the liver pâté, the hare pâté, in yellow terrines.” (Le Ventre de Paris).

In France, a good terrine is usually eaten as a starter or with an apéritif, alongside crunchy cornichons, a leaf of salad, and mustard. More and more often in what are now called néo-bistrots, pickles are added on the side for acidity and color. Bread is not mandatory, but personally, I’d say it’s essential. A good country loaf, with a thick crust and moist crumb, is always necessary, isn’t it?

It’s also important not to confuse terrine with pâté. In cooking, a pâté is a preparation of meat, fish, or vegetables, minced and spiced, then baked inside pastry. A terrine, on the other hand, is cooked in a terrine: it’s all in the container.

Recipe: la terrine tout cochon by Rodolphe Paquin for Le Fooding

Ingredients (serves 8)

1.5 kg fresh pork belly

1 kg pork jowl

500 g pork liver

3 shallots

2 garlic cloves

2 eggs

2 cl cognac

10 g fine salt

3 g crushed black pepper

1 bunch fresh thyme

2 bay leaves

Method

Grind the meats in a meat grinder fitted with a medium plate. Add the finely chopped shallots and garlic.

Stir in the beaten eggs, cognac, salt, and pepper. Mix well until you have a smooth stuffing.

Fill a terrine with the mixture, pressing it down lightly.

Place the thyme and bay leaves on top.

Set the terrine in a water bath and bake in a preheated oven at 160 °C (320 °F) for about 1 hour 30 minutes. Test for doneness by inserting a skewer: the juices should run clear.

Let cool, then refrigerate for at least 24 hours before serving.

U - Uniformisation

Uniformisation plays out at several speeds.

The first is globalization: chains backed by investment funds, never truly independent, setting up everywhere, driving prices up, and smoothing out their offers to make them accessible to the largest possible audience. In Paris, the world’s most visited city, this translates into consensual dishes, bland, risk-free.

Théophile Gautier was already poking fun at this: “Could it be at Chevet’s that Vitellius’s hefty tripe-eater would find what he needed to fill his famous Minerva shield with pheasant and peacock brains, flamingo tongues and scarrus livers?”

Uniformisation also means the gradual erasure of the know-how that once made French culinary culture rich and diverse. Meat consumption illustrates this clearly: on plates, it’s always the same cuts, leading to absurd waste; in prepared foods, the cuts disappear altogether, as if we preferred not to see them. In the past, every artisan had a role: the butcher for beef, the charcutier for pork, the tripier for offal. The whole carcass of an animal was used, reducing waste and multiplying culinary experiences.

At what point did we decide that these foods — liver, kidneys, tripe — were less noble, less edible, than standardized products whose harmful effects we now measure daily? Meat today often ends up hidden inside ultra-processed, polluting, harmful, interchangeable foods. If France remains one of the European countries with the lowest obesity rates (9.7%, compared with 26.8% in the UK and 42% (!) in the US), it’s also thanks to the survival of diverse culinary traditions, which still make home cooking possible and offer an escape from uniformisation through industrial transformation. Recognizing this is key to ensuring they endure. It’s a matter of public health, ecology, and taste diversity.

Uniformisation also means words emptied of meaning through overuse: cafés “de spécialité,” wines “vivants,” menus labeled “authentic.” It’s the monotony of restaurants forced by ingredient costs to always cook the same proteins: pork shoulder, pollock, calamari. As André Leroi-Gourhan noted, “Uniformisation is already well advanced, and men’s and women’s clothing, from one class to another, is distinguished only by greater or lesser monetary value and more or less immediate adaptation to fashion.”

And then there’s uniformity in unanimity: spots hyped by a TikTok influencer, lines outside Cédric Grolet’s pastry shops, dishes designed for photography. Gautier foresaw it: “When everything is the same, travel will become completely useless.”

Yet there are still breathing spaces. Often out in the countryside, you stumble upon singular experiences like mushrooms by the roadside. There, the constraints aren’t financial but tied to access, land, and seasons — and within those limits, flashes of real creativity appear. I think of a broth I had at Maison Ailhon, where the chef slipped in pieces of pig’s ear cut like crozets: maybe the best dish I ate all year.

And if I soften the verdict further, Paris still has its exceptions — Café du Coin, Café de l’Usine, or Ama Siam are all places that escape the dullness of uniformisation.

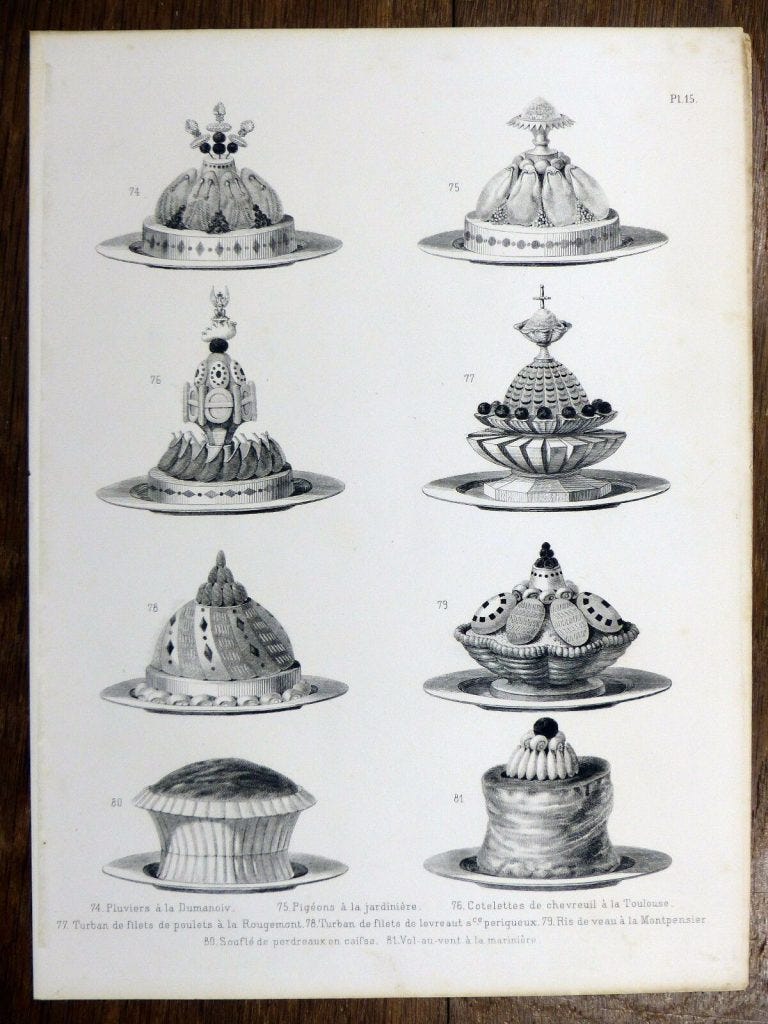

V - Vol-au-vent

The vol-au-vent has its roots in Belgian tradition, later polished and elevated in France. En Europe, the broader idea of enclosing a filling in pastry was already widespread, with french famourse variations such as pâté de Chartres, pithiviers, puits d’amour, mille-feuille, or bouchée à la reine. In the early 19th century, Antonin Carême — the “roi des chefs et chef des rois” — gave the vol-au-vent its canonical form by codifying the recipe and systematizing the use of puff pastry, turning it into a pillar of grande cuisine.

By replacing the heavy doughs of earlier pies with puff pastry so light it could, as people said, “fly in the wind,” Carême secured the name and established the vol-au-vent as a symbol of refinement: a golden, hollow case filled with a creamy garnish — often poultry, quenelles, or mushrooms bound in velouté sauce.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to get lost in France to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.