It’s a first-world problem, I know, but as a journalist I often get wine I never asked for. My kitchen isn’t big, and it ends up cluttered with bottles I’ll never drink and don’t know what to do with.

I don’t love wine enough to love it in all its forms. A decent supermarket bottle doesn’t taste the same to me. What makes me love wine, above all, is a whole approach, a relationship of the closest intimacy between a soil and my palate. Usually, I only accept one middleman: the winemaker. Sometimes two, when I sense that a wine merchant or sommelier has that same intimate connection and enough sensitivity to share it.

A bad wine, in my book, is one produced to meet a standard designed for markets. That’s true at both ends of the spectrum. On one side, wines made to obey Parker’s diktats—big, boozy, uniform, and packed with sulfites. On the other, hipster-bait bottles full of flaws: mousey notes, volatile acidity, funky barnyard. These wines only exist to serve image-conscious drinkers who want to blend into a crowd.

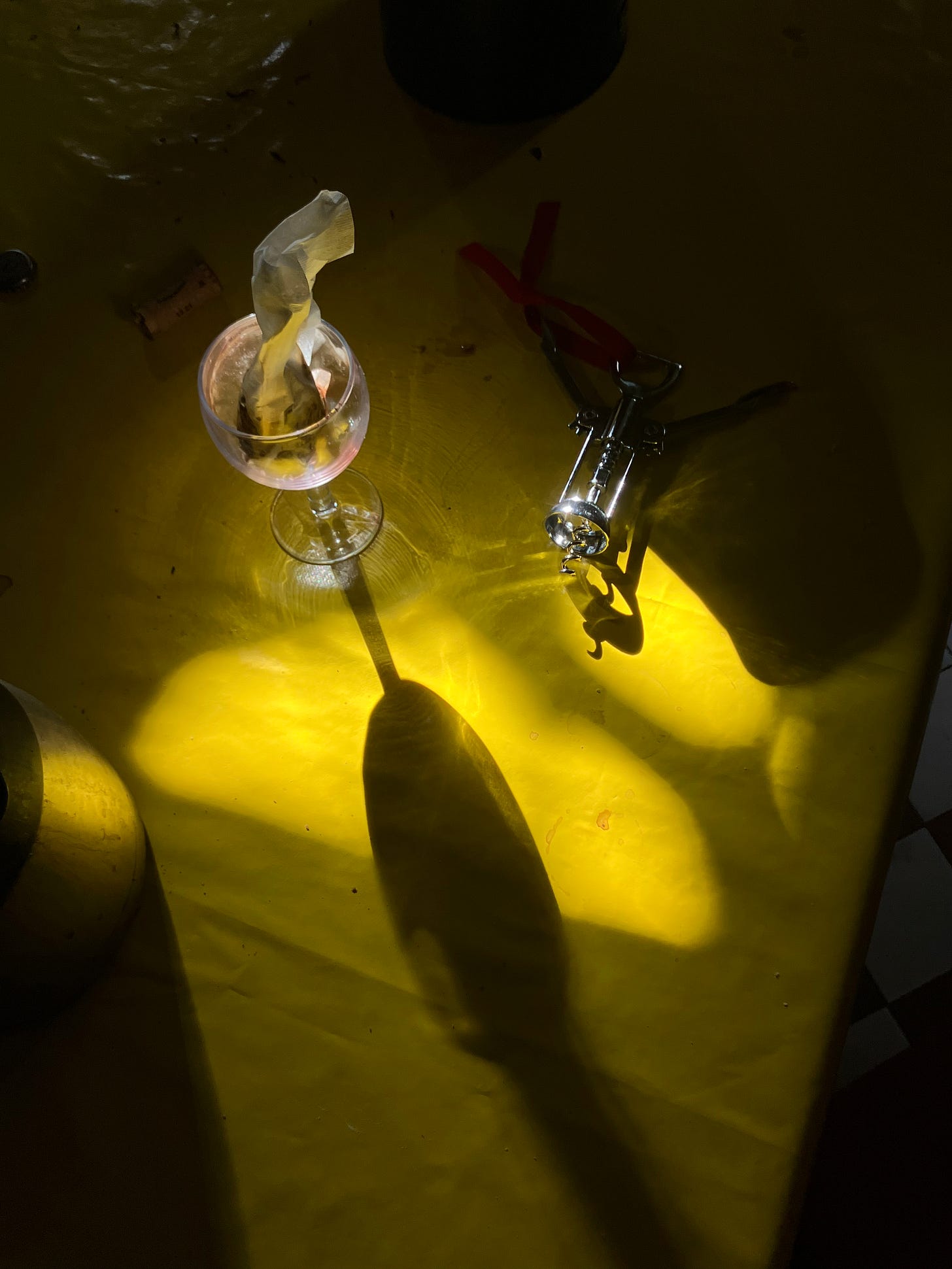

Here are 7 ways to make use of bad wine

1. Dyeing with wine and lees

It’s easy to forget that wine (especially red) was once widely used as a dye. Anthocyanin, the grape’s natural pigment, produces a range of reds and purples that vary in intensity depending on the acidity of the bath. Reduced, wine becomes an ink or a fragile dye, unstable in light yet sufficient to tint leather, fabric, or wood. Lees, richer in pigment, were often used for these domestic purposes. Even today, some artisans and dyers are rediscovering these residues to give natural shades to wool or linen, embracing their fleeting character.

Drunkard’s dye — a simple method

Wash the fabric or wool thoroughly with mild soap to remove any finish. Rinse well.

Prepare a large pot with enough red wine (or a wine + lees mixture) to cover the fiber.

Bring to a simmer, then turn off the heat.

Submerge the damp textile in the wine bath. Let it soak for 4 to 24 hours, stirring occasionally.

For deeper color, reduce the wine to one-third before immersing the fiber, or add a bit of filtered lees.

Once the desired shade is reached, rinse in cold water until the water runs clear.

Lay flat to dry in the shade, to slow fading.

The result ranges from red to purple to brown, depending on the material and soak time. The colors are fragile in light and with repeated washing, but they carry a raw, boozy, and fleeting charm true to their origin.

2. Cooking with mediocrity

A bad wine can be turned into a cooking tool (even if a good wine will be better to do so). Poured into a pot of beef bourguignon, it disappears behind meat juices, herbs, and hours of slow cooking. In tomato sauce, it adds the acidity missing from winter tomatoes. In a marinade, it tenderizes more than it flavors. In the kitchen, wine becomes nothing more than acidic, alcoholic matter. You don’t expect it to have a soul anymore, you are just looking for a function.

Bistro-style shallot and red wine sauce

Ingredients

2 finely chopped shallots

1 crushed garlic clove

10 g (about 2 tsp) butter

500 ml (2 cups) medium red wine

1 bay leaf

2 sprigs thyme

Cracked black pepper

A pinch of sugar

400 ml (1 ½ cups) beef or veal stock

Salt, Espelette pepper optional

Method

Sweat shallots and garlic in butter without browning.

Deglaze with wine, add bay leaf, thyme, and pepper. Bring to a simmer.

Reduce at a rolling boil until one-third remains.

Add the stock. Simmer until the texture coats the back of a spoon.

Adjust seasoning with salt, sugar (if too acidic), and optional chili.

Strain through a fine sieve and keep warm. Serve over skirt steak, hanger steak, sautéed mushrooms, or roasted vegetables.

3. Reduction, the last gasp

Before heading down the drain, some wines can still face the trial by fire. Reduce them—alone or with sugar and spices—to make a sweet-and-sour syrup. Paired with pears, figs, or game, this concentrate plays its final role. Reduced, bad wine becomes discreet, almost useful. Honey, I shrunk the plonk.

4. Sangria, mulled wine, and other disguises (not for me, please)

This is the popular version of redemption. A bad wine drowned under citrus, cinnamon, sugar, and sometimes a splash of hard liquor disappears. Sangria and mulled wine are recipes for forgetting. You’re not drinking wine anymore—you’re drinking a party backdrop. Which is exactly why I never drink sangria.

5. Vinegar or nothing

A failed wine can sometimes be reborn as vinegar. Acetic fermentation transforms alcohol into acetic acid, and the liquid finally takes on a noble role. But beware: a conventional wine, saturated with sulfites and additives, resists that transformation. Don’t use it for this. Only “living” wines, already near the turning point (don’t be offended), are ready to let bacteria move in.

Homemade vinegar, step by step

Before starting, pick a wine with little or no sulfites. If the alcohol level is too high, you can dilute it slightly with non-chlorinated lukewarm water.

Equipment

An earthenware jar or vinegar crock

Cloth and a rubber band

A vinegar mother or a splash of raw unfiltered vinegar

Procedure

Pour about 750 ml (3 cups) of wine into the jar. If alcohol is above 12–13%, dilute with a little water. Add the mother or raw vinegar.

Cover with cloth to let air in and place in a dark spot at room temperature.

Wait 2–3 weeks. A gelatinous film—the “mother”—may form. Taste regularly until acidity is where you want it.

Draw off what you need, keep some vinegar and the mother, then feed with more leftover wine.

Filter if needed and bottle.

6. The false promise of recycling (this is not really an option)

You often read that wine can be used as fertilizer, stain remover, or cleaning product. Illusion, trickery, nonsense! Pouring an alcoholic, acidic liquid on your plants is rarely a gift. Cleaning copper with Bordeaux? Pure folklore. The truth is simpler: bad wine is still a mistake, and sometimes the only reasonable end is the sink.

7. The joy of giving (and getting rid of it)

Because wasting bottles down the sink is not an option, the most elegant solution is to delegate taste. Give away wine that doesn’t move you to those who actually enjoy it. A big Bordeaux to my partner’s grandmother, supermarket champagne for the birthday party I had no wish to attend, a seriously funky natural wine to my friend in a cap and mustache who swears this is the real deal. The right pairing is, first and foremost, a social pairing. You give pleasure, you free your kitchen—and you make room for good bottles.